Federal wire fraud, under 18 U.S.C. § 1343, is an allegation that fraud has been committed by using some kind of electronic communication. This type of electronic communication is construed broadly and can range from a fax, telephone, email, electronic messaging, use of electronic payment systems, and more. Common examples of wire fraud include internet “phishing” scams, operating a misleading website, or accepting electronic payment for a fraudulent transaction.

Because so much business is conducted using electronic communication, the wire fraud statute is commonly used by the government in the investigation and prosecution of economic or “white collar” criminal cases. For example, criminal investigations often begin with a wire fraud inquiry, and other, more specific, fraud charges (such as healthcare or tax fraud, etc.) are brought later on as a result of that investigation.

Elements of Wire Fraud

To establish wire fraud, the government must prove that the accused intentionally used some kind of electronic communication with the purpose of committing fraud. More specifically, the wire fraud statute, found in 18 U.S.C. § 1343, provides as follows:

Fraud by wire, radio, or television

Whoever, having devised or intending to devise any scheme or artifice to defraud, or for obtaining money or property by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises, transmits or causes to be transmitted by means of wire, radio, or television communication in interstate or foreign commerce, any writings, signs, signals, pictures, or sounds for the purpose of executing such scheme or artifice, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both. If the violation occurs in relation to, or involving any benefit authorized, transported, transmitted, transferred, disbursed, or paid in connection with, a presidentially declared major disaster or emergency (as those terms are defined in section 102 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. § 5122)), or affects a financial institution, such person shall be fined not more than $1,000,000 or imprisoned not more than 30 years, or both.(1)

Courts break down wire fraud into three elements, requiring that the defendant: “(1) devised or willfully participated in a scheme to defraud, (2) used an interstate wire communication in furtherance of the scheme, and (3) intended to deprive a victim of money or property.”(2) The deprivation of property must be an object of the scheme, not merely incidental to it.(3)

Typically, the element at issue in a wire fraud case is intent. The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals recently addressed this element in United States v. Montgomery, explaining that “[d]irect evidence of fraud can be scarce, so a factfinder may consider circumstantial evidence of fraudulent intent and draw reasonable inferences therefrom.”(4) For example, fraudulent intent “can be inferred from efforts to conceal the unlawful activity, from misrepresentations, from proof of knowledge, and from profits.”(5)

The recent Montgomery case, currently on appeal to the United States Supreme Court, serves as an example of how fraudulent intent can be inferred. There, five defendants were charged and convicted with various counts of fraud, including wire fraud. The defendants were drug marketers that allegedly convinced friends and family to order prescription creams and wellness tablets that they did not need, and then pocketed a portion of the insurance reimbursement for themselves.

On appeal, the Sixth Circuit explained that the defendants’ intent to defraud could be inferred from the following evidence: the defendants targeted individuals who had insurance that would not scrutinize the prescriptions at issue; the defendants paid individuals to order the creams and pills; the defendants created pre-set order pads with drug formulas tailored to maximize their profit; they persuaded customers to order unneeded and unwanted creams; they ordered extra creams and refills for customers without their knowledge or consent; they paid medical providers to sign prescriptions without seeing patients; and they directed pharmacists to backdate prescriptions to ensure the drugs were covered by insurance. Such actions, explained the Sixth Circuit, “constitute[ed] an intentional, comprehensive scheme to defraud and establish the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.”(6)

Conspiracy to Commit Wire Fraud

It is also important to note that, if more than one person is involved in the alleged wire fraud, federal prosecutors will often bring conspiracy charges under U.S.C. § 371 and 18 U.S.C. §1349 as well. A conspiracy to commit wire fraud requires that two or more persons conspired, or agreed, to commit wire fraud and the defendant knowingly and voluntarily joined the conspiracy.(7)

In the Sixth Circuit, “the government is not required to allege all of the elements of the underlying substantive offense [e.g. wire fraud] when charging a conspiracy under § 371.”(8) Instead, the Sixth Circuit has held that, in the instance of a charge of conspiracy to commit fraud, “the government merely ha[s] to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that [the defendant] knowingly and voluntarily joined a conspiracy that intended to fraudulently obtain money and that a member of the conspiracy took at least one overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.”(9)

Fraud Prosecution and Litigation Statistics

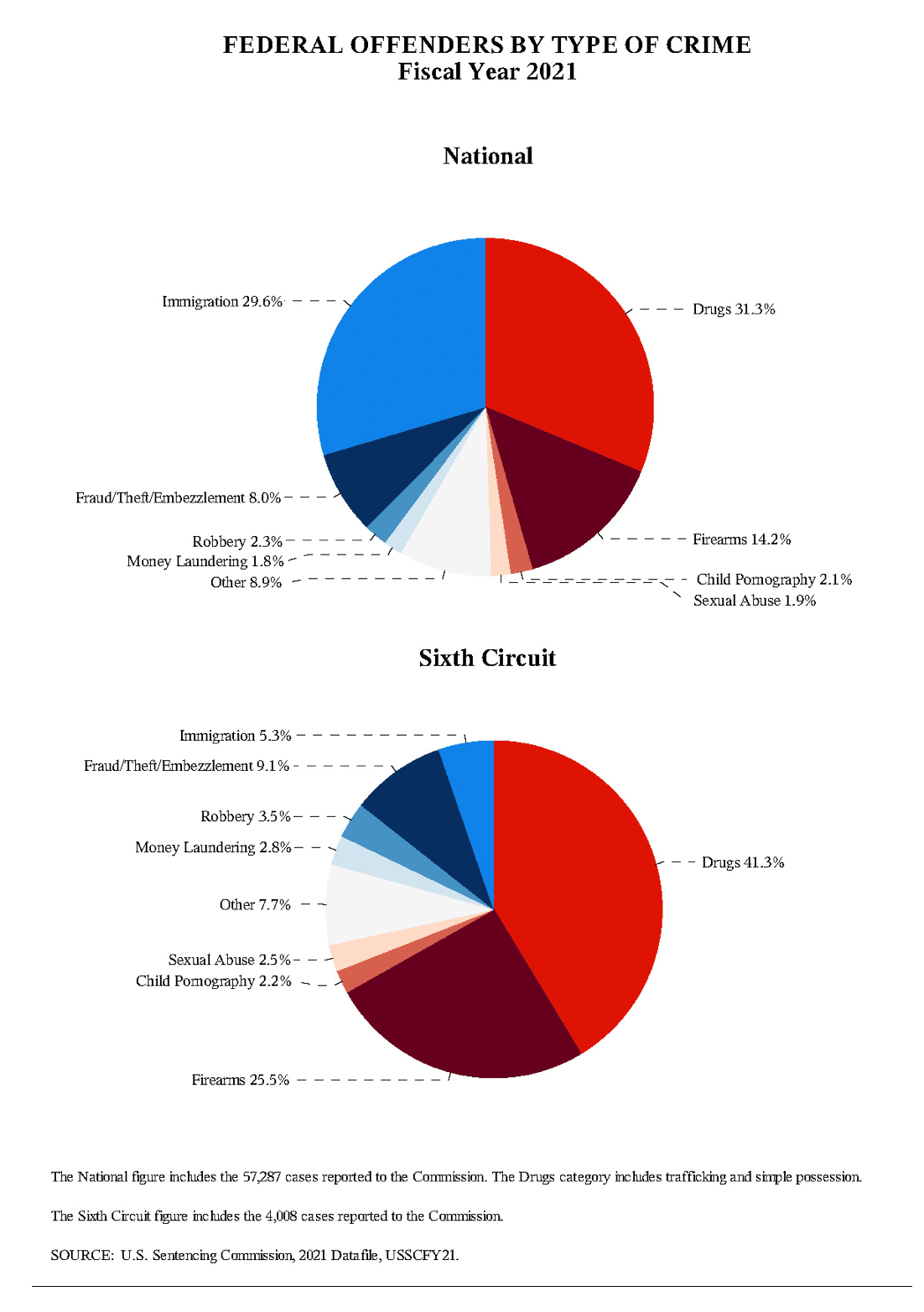

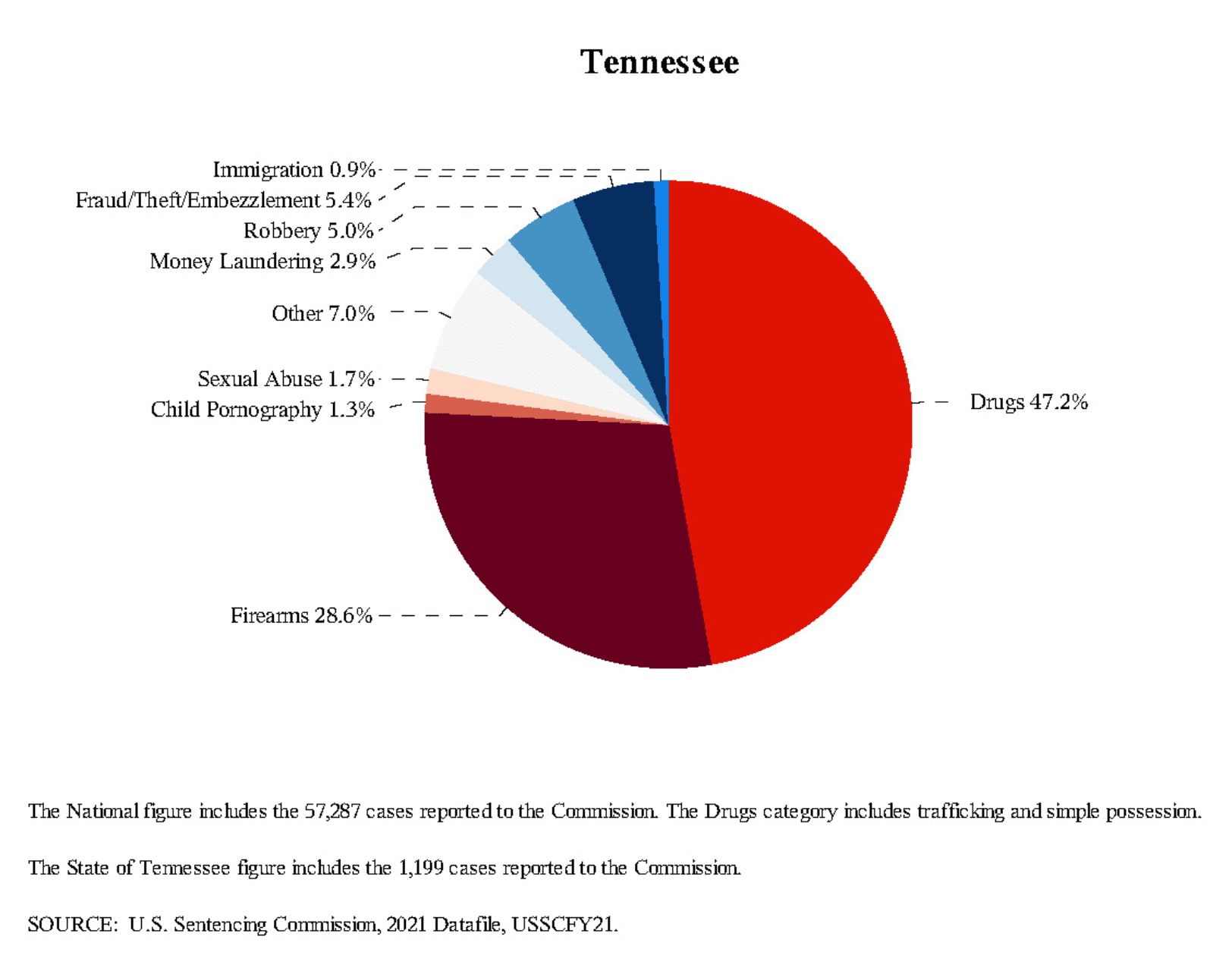

In the United States in 2021, fraud/theft/embezzlement cases amounted to 4,571 or 8% of federal crimes charged. In the Sixth Circuit, that figure is over 9%, with 365 cases that year.(10) In Tennessee, that is 65 or 5.4% of cases(11).

The large majority of these cases result in guilty pleas. As for the resolution of these cases in 2021, nationally 4,469 (or 97.8%) of these cases resulted in a plea of guilty, with 102 (2.2%) being tried. In the Sixth Circuit, 360 (or 98.6%) of these cases resulted in a plea of guilty, with 5 (1.4%) (12)being tried. In Tennessee, 64 (or 98.6%) resulted in a plea of guilty, with 1 (or 1.4%) being tried. (13)

Sentencing

A single act of wire fraud is punishable for up to 20 years in prison, a fine, or both. In certain situations, this felony is punishable for up to 30 years in prison, a fine, or both. Sentencing in wire fraud cases is highly dependent upon the facts of the case and the character and history of the accused.

As for sentencing data, nationally, individuals convicted of fraud/theft/embezzlement are given an average of 20 months. In the Sixth Circuit, individuals convicted of fraud/theft/embezzlement are sentenced to an average of 15 months.(14) In Tennessee, the average sentence is 21 months.(15)

The district courts arrive at these sentences by using the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. These guidelines are an advisory set of recommendations aimed at ensuring uniform sentencing. They provide a method for arriving at a range of months (called a “guideline range”) and then offer some recommendations for departing from this range in certain situations (increasing or decreasing the sentence). Most wire fraud charges fall under Federal Sentencing Guideline § 2B1.1. Generally, factors that can impact a defendant’s sentence under the wire fraud statute include (but are not limited to) the loss amount, the number of victims, any infliction of emotional harm, the defendant’s criminal history, any substantial assistance to authorities, and more.

As related to the guideline ranges, nationally, individuals convicted of fraud/theft/embezzlement are sentencing within the guideline range 42.9% of the time.

In the Sixth Circuit, individuals convicted of fraud/theft/embezzlement are sentenced within the guideline range 39.7% of the time.(16) In Tennessee, individuals are sentenced within the guidelines range 37.5% of the time. (17)Accordingly, the data shows that district judges are willing to issue sentences outside of the guideline ranges if presented with effective arguments at sentencing.

Conclusion

With decades of experience litigating “white collar” crimes and defending individuals charged with fraud, the legal team at Davis & Hoss is ready to help individuals facing potential allegations of wire fraud or those that simply have questions. Contact Attorney Lee Davis at lee@davis-hoss.com or by phone at 423-266-0605 for more information.

Reference:

- 18 U.S.C. § 1343

- United States v. Rogers, 769 F.3d 372, 377 (6th Cir. 2014).

- Kelly v. United States, 140 S. Ct. 1565, 1573 (2020).

- United States v. Montgomery, No. 20-5891, 2022 WL 2284387, at *9 (6th Cir. June 23, 2022) (citations, internal quotations, and punctuation omitted).

- Id. (citations, internal quotations, and punctuation omitted).

- Id.

- United States v. Palma, 58 F.4th 246, 249 (6th Cir. 2023) (citations, internal quotations and punctuation omitted).

- United States v. Henderson, No. 3:22-CR-14-TAV-JEM-1, 2022 WL 17061070, at *7 (E.D. Tenn. Nov. 17, 2022) (motion to dismiss denied).

- Id. (citing United States v. Washington, 715 F.3d 975, 980 (6th Cir. 2013)).

- United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, Sixth Circuit, Figure A, p. 1; Table 1 p. 3

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/6c21.pdf - United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, State of Tennessee, Figure A, p. 1; Table 1, p.3

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/tn21.pdf - United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, Sixth Circuit, Table 3, p. 7

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/6c21.pdf - United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, State of Tennessee, Table 3, p.7

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/tn21.pdf - United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, Sixth Circuit, Table 7, p. 11

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/6c21.pdf - United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, State of Tennessee, Table 7, p. 11

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/tn21.pdf - United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, Sixth Circuit, Table 10, p. 16

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/6c21.pdf - United States Sentencing Commission Statistical Information Packet, Fiscal Year 2021, State of Tennessee, Table 10, p. 16

https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/federal-sentencing-statistics/state-district-circuit/2021/tn21.pdf